EXPECTATIONS AND PLACEBO

Expectation is a very pervasive psychological and social phenomenon. It is, in fact, a very generic term that can be defined from several different points of view. As we will write in a short while, the expectations generated by being in treatment can change the patient’s brain and, as a consequence, the very outcome of medical treatments themselves. Therefore, because of its deep clinical implications, the study of expectations has gained a fundamental role in modern neuroscience.

What to expect from the physical world

With expectation we refer to the more or less accurate anticipation that individuals formulate on a certain event. Despite not being fully aware of it, we develop expectations on more or less everything around us including both physical and psychological events. We expect a desk to have a certain solidity, a glass to weigh around 200 grams and that its weight will be inferior to that of a bottle; we expect a certain repertoire of responses to each action. It is often hard to realize how many expectations we have on the world around us as we take them for granted in our everyday life. On the contrary, it is much easier to realize that we had certain expectations when they are broken. Going back to the example of the glass, if we would grab one that weighs 1 kg, we would be surprised, because our expectation on weight would be different from the facts. Our behaviors therefore, are heavily influenced by the expectation we have on events.

What to expect from the treatment context

Just as we have many expectations regarding the physical world, our brain elaborates several hypotheses on relational contexts, such as the therapeutic one. An interesting research field focuses on expectations that patients have in psychological treatments. More specifically, researchers are trying to investigate the role of expectations in the field of the complex doctor-patient relationship, and thus, in the complex context of treatments. If, as noted earlier, the doctor-patient relationship and the therapeutic outcome of treatments (both medical and psychological ones) depend to a certain extent on the expectation that the patient has toward therapy, the management the patient’s expectations must be viewed as an activity of preeminent relevance for the physician-therapist, as important as the planning of a proper treatment plan.

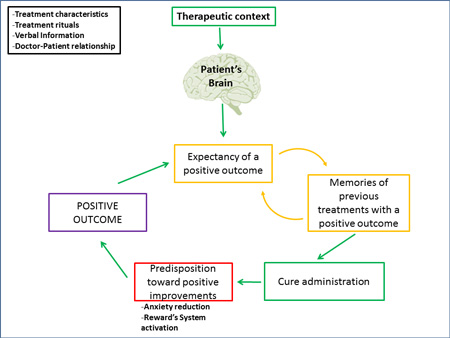

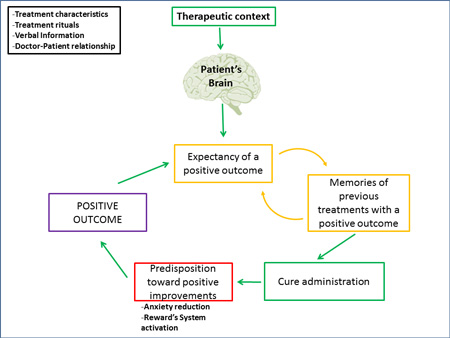

Recent studies on placebo effect enormously contributed to the comprehension of the laws underlying expectation. In fact, in common language, “placebo effect” and “expectation effect” are often used as synonyms. When mentioning placebos we are referring to a substance or, more generally, to a treatment, which is inert from the medical-pharmacological point of view and that is administered to appease a patient. Despite the fact that placebos do not contain, by themselves, an active ingredient, when patients receive them, they may feel a true improvement of their medical condition (e.g. a true reduction of painful sensations). This is what is called placebo effect. More generally, when we administer a medical treatment, it is very important to be aware that such treatment is administered in a context: the treatment context. Such context, which includes the physical aspect of the cure (such as the shape and color of pills), the administration ritual, the verbal information provided by the medical staff and the relationship that the patient builds with it, generates expectations. When substituting an active drug with a placebo, the context of treatment remains the same together with the expectations the patients have on the outcome of therapy. Therefore, the study of placebo is the study of the context in which a medical treatment takes place and of the effects that this context has on the patient’s brain (Carlino et al. 2014).

Several factors influence the expectations that patients develop, such as the verbal interactions with other patients or therapists, the emotions felt during treatment and the previous therapeutic experiences. For instance, the more “strong” the words used by the physician during the administration of a placebo lotion meant alleviate pain, the higher the expectations of pain reduction patients will have and, as a consequence, the stronger the analgesic effect they will feel after the application of the lotion. The reduction of anxiety that the patient feels when hearing the voice of the doctor, the activation of the reward system that corresponds to the anticipation of a clinical improvement, interact with expectations and contribute to the modification of the patient’s brain. Obviously, in each of these examples, we must always consider the role of the relationship between patient and doctor: the more trust and respect the patient feels toward his/her doctor, the more positive clinical changes will occur.

From a psychological standpoint, research showed that expectations are heavily influenced by past experiences. To explain this phenomenon we can refer to the classical example of Pavlovian conditioning. Such model states that after several exposures to a neutral stimulus (e.g. a sound) associated with an unconditioned stimulus (e.g. food), which by itself produces a response (salivation), presenting just the neutral stimulus will lead to the same response. It is possible to elicit placebo effect by using the same conditioning principles. For instance, it has been observed that certain specific aspects of a treatment, such as the shape of drugs, can induce conditioned placebo responses if that shape had been previously associated to effective active ingredients. That means that repeated administration of a treatment induces in patients specific expectations on the treatment itself: for example, the administration of morphine induces a reduction of pain and thus a future expectation of pain reduction for future administrations. Such expectations and predispositions make the treatment work even if it consists in a sugar pill. In a study that was conducted with functional magnetic resonance, it has been proved that the expectation of pain reduction is built with the passing of time: the more time passes, the less pain is felt, the more intense the activation of certain brain areas that seem to be implicated in processing expectations: more specifically the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the cingulate anterior cortex (Lui et al., 2010).

From the neurophysiological standpoint, the belief that what we receive is what we expect is increasingly supported by different researches. When a patient is expecting to receive an analgesic drug, he/she activates the brain pain modulatory system just as if he/she were receiving the drug. In many studies, researchers administered opioid painkillers, such as morphine or remifentanil. In such studies, after having purposely induced pain, the authors compared the brain activation caused by the administration of a painkiller (such as remifentanil) with that caused by the administration of a placebo that the patient considered a real analgesic. Results show that both groups (remifentanil group and placebo group) reported a reduction in pain levels. In the brain, the areas that were activated by the drug and by the placebo were very similar: in both cases a reduction in the activation of the brain areas involved in pain perception, that is a system called “pain matrix”, which includes the thalamus, the insula, the rostral part of the anterior cingulate cortex, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the primary somatosensory cortex, the supramarginal gyrus and the left parietal lobule. Furthermore, in the placebo group, a greater activation of frontal areas and of the above-mentioned prefrontal dorsolateral and anterior cingulate cortices has been observed (Petrovic et al., 2005, 2010). Such areas, in fact, are involved in the elaboration of superior brain functions, such as planning and abstract reasoning and have a crucial role in the processing of expectations.

Implications for clinical practice and hypnosis

Maybe, one of the most interesting demonstrations that expectation is a crucial factor in therapy comes from the researches using the so-called “open-hidden” protocol. Let’s picture a patient who is attached to an infusion pump that releases a specific anesthetic in certain moments of the day. The patient will know that the anesthetic will be released but he/she doesn’t know when (hidden). In this protocol, a therapy can be administered without providing any verbal information signaling the administration (open administration). Therefore the patient, doesn’t expect any kind of improvement and this absence of expectation leads to a true reduction of therapeutic effectiveness (Benedetti, Carlino & Pollo, 2011).

The open-hidden model suffers from the disadvantage of being very hard to apply from a methodological point of view but has the enormous advantage to lie on the border between experimental context and clinical practice. It has been demonstrated, for instance, that the effectiveness of diazepam, one of the most frequently used benzodiazepines in the treatment of anxious conditions, is greatly reduced or completely abolished when administered without the patient’s awareness, that is in a hidden modality (Benedetti, Carlino & Pollo, ibid.). Another “historical” example comes from dental practice: it has been observed that, after a third molar extraction, the anesthetic effects of an intravenous injection of 6-8 mg of morphine (hidden administration) corresponded to those generated by the injection of a saline solution (placebo) openly administered to the patient. In conclusion, when patients expected to receive an anesthetic, the effects were so strong that they felt the same effect of 6-8 mg of morphine.

From a clinical point of view, these studies lead to emphasize the idea that the knowledge the patient has about the treatment does influence the treatment itself. One could, for example, think to openly begin the administration of a drug, increasing its effectiveness, to then cease it according to a hidden protocol in order to reduce the negative expectations related to the end of the treatment. A recent survey on the Italian population showed that the most important preoccupation for patients in the sample is related to the doctor-patient relationship and, more specifically, it concerns the information about the effectiveness of the therapy that they are going to receive. In light of these studies, we should expect that all therapies that are not administered with adequate information and that do not create (ethical) positive expectations, will end up to be weakly effective for patients (Frisaldi & Piedimonte, 2014).

We must consider that the doctor-patient relationship is always influenced by words and attitudes that channel strong expectations toward the treatment program. Together with patients’ expectations, in fact, a better interaction with the doctor leads to better therapeutic adherence up to the point that the number of medical exams can be considered as an index to measure the improvement (for a review of the literature on the doctor-patient relationship: Benedetti, 2012). Therefore, the trust that patients feel toward their doctor, their opinion on his/her experience and also (maybe above all) the human relationship between them, are all factors that lead to more positive therapeutic outcomes.

About the connection between placebo and hypnosis, the latter may be used as a tool, explicitly used, to manage expectations in order to produce therapeutic effects. An interesting way to define hypnosis is that of a “non deceitful placebo” (Kirsh, 1994). Considering this definition and interpreting hypnosis in the frame of placebo effect, the crucial factor of therapeutic sessions may be constituted by the construction of a context that elicits placebo effects in patients without the use of “true” placebos and thus creating expectations towards change through verbal and contextual relationship.

Interestingly, several studies compared the effects of hypnosis with those caused by a placebo response in different clinical contexts. More specifically, it has been showed that both hypnosis and placebos produced comparable pain reductions in the treatment of headaches (Spanos et al, 1993). In studies targeting experimentally induced pain (where pain is “artificially” produced by means, for example, of a cuffthat tightens around the arm of participants), researchers showed that subjects who are less susceptible to hypnosis obtained similar pain reductions when receiving hypnosis or a placebo. On the contrary, patients who were highly susceptible to hypnosis showed a greater pain reduction after just one hypnosis session compared to that felt following the administration of a placebo (Frischholz, 2007).

Therefore, if on the one hand it seems that the effects generated by placebos and hypnosis are very similar, on the other, there surely are some substantial differences between the two mechanisms, unfortunately still poorly examined by scientific research.

From a neuroscientific point of view, neuro-imaging techniques (techniques that allow us to visualize the in-vivo activity of the brain) showed some interesting “cerebral parallels” between hypnosis and placebo effect. As highlighted in previous paragraphs, several studies have pointed to the relevant activation of the anterior cingulate cortex (area of emotion processing) and of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (which has a role in planning future complex behaviors) that occurrs during hypnosis sessions and these same areas appear to be active during placebo responses (Frisaldi & Piedimonte, ibid.).

Concerning the effects of hypnosis, it has been showed that these produce a brain pattern that consists primarily in the reduction of activity in a network called “default mode network” (McGeown et al. 2009). Such network, which includes frontal and subcortical structures, is constituted by a group of areas that are believed to be active when individuals are not involved in any specific cognitive task (problem solving, planning behavior, etc…) but, instead, they let their minds “wander” in a relaxed state. A reduction in the activity of these areas means an active shift of attention toward the suggestion the therapist is providing that, maybe, can reflect the construction of expectations on the session. This study in particular demonstrates that hypnosis is not a passive phenomenon in which there is a sender and a receiver, but, on the contrary, it is a constructive process where clients actively listen to the words of the therapist and build their hypotheses about the relationship.

The study of how mechanisms similar to the placebo response act and interact within the hypnotic phenomena, while being a big challenge, can lead us to understand which brain areas are involved in the generation of a positive expectation and, more generally, to develop approaches that can increasingly be tailored on patients to enhance the positive outcome of a (psycho)therapy.

References

Benedetti, Fabrizio, Elisa Carlino, and Antonella Pollo. “How Placebos Change the Patient’s Brain.” Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 36, no. 1 (January 2011): 339–54. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.81.

Carlino, Elisa, Elisa Frisaldi, and Fabrizio Benedetti. “Pain and the Context.” Nature Reviews Rheumatology 10, no. 6 (June 2014): 348–55. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2014.17.

Frisaldi, Elisa, Alessandro Piedimonte, and Fabrizio Benedetti. “Placebo and Nocebo Effects: A Complex Interplay Between Psychological Factors and Neurochemical Networks.” American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 57, no. 3 (July 3, 2015): 267–84. doi:10.1080/00029157.2014.976785.

Frischholz, Edward J. “Hypnosis, Hynotizability, and Placebo.” American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 50, no. 1 (July 1, 2007): 49–58. doi:10.1080/00029157.2007.10401597.

“Il Cervello Del Paziente - Benedetti Fabrizio - Libro - Giovanni Fioriti Editore - - IBS.” Accessed January 24, 2015. http://www.ibs.it/code/9788895930497/benedetti-fabrizio/cervello-del-paziente.html.

Levine, Jon D., Newton C. Gordon, Richard Smith, and Howard L. Fields. “Analgesic Responses to Morphine and Placebo in Individuals with Postoperative Pain.” PAIN 10, no. 3 (June 1981): 379–89. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(81)90099-3.

Lui, Fausta, Luana Colloca, Davide Duzzi, Davide Anchisi, Fabrizio Benedetti, and Carlo A. Porro. “Neural Bases of Conditioned Placebo Analgesia.” Pain 151, no. 3 (December 2010): 816–24. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.021.

McGeown, William J., Giuliana Mazzoni, Annalena Venneri, and Irving Kirsch. “Hypnotic Induction Decreases Anterior Default Mode Activity.” Consciousness and Cognition 18, no. 4 (December 2009): 848–55. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2009.09.001.

Spanos, Nicholas P., Sharon J. Liddy, Heather Scott, Catherine Garrard, Joy Sine, Angela Tirabasso, and Amber Hayward. “Hypnotic Suggestion and Placebo for the Treatment of Chronic Headache in a University Volunteer Sample.” Cognitive Therapy and Research 17, no. 2 (April 1, 1993): 191–205. doi:10.1007/BF01172965.

What to expect from the physical world

With expectation we refer to the more or less accurate anticipation that individuals formulate on a certain event. Despite not being fully aware of it, we develop expectations on more or less everything around us including both physical and psychological events. We expect a desk to have a certain solidity, a glass to weigh around 200 grams and that its weight will be inferior to that of a bottle; we expect a certain repertoire of responses to each action. It is often hard to realize how many expectations we have on the world around us as we take them for granted in our everyday life. On the contrary, it is much easier to realize that we had certain expectations when they are broken. Going back to the example of the glass, if we would grab one that weighs 1 kg, we would be surprised, because our expectation on weight would be different from the facts. Our behaviors therefore, are heavily influenced by the expectation we have on events.

What to expect from the treatment context

Just as we have many expectations regarding the physical world, our brain elaborates several hypotheses on relational contexts, such as the therapeutic one. An interesting research field focuses on expectations that patients have in psychological treatments. More specifically, researchers are trying to investigate the role of expectations in the field of the complex doctor-patient relationship, and thus, in the complex context of treatments. If, as noted earlier, the doctor-patient relationship and the therapeutic outcome of treatments (both medical and psychological ones) depend to a certain extent on the expectation that the patient has toward therapy, the management the patient’s expectations must be viewed as an activity of preeminent relevance for the physician-therapist, as important as the planning of a proper treatment plan.

Recent studies on placebo effect enormously contributed to the comprehension of the laws underlying expectation. In fact, in common language, “placebo effect” and “expectation effect” are often used as synonyms. When mentioning placebos we are referring to a substance or, more generally, to a treatment, which is inert from the medical-pharmacological point of view and that is administered to appease a patient. Despite the fact that placebos do not contain, by themselves, an active ingredient, when patients receive them, they may feel a true improvement of their medical condition (e.g. a true reduction of painful sensations). This is what is called placebo effect. More generally, when we administer a medical treatment, it is very important to be aware that such treatment is administered in a context: the treatment context. Such context, which includes the physical aspect of the cure (such as the shape and color of pills), the administration ritual, the verbal information provided by the medical staff and the relationship that the patient builds with it, generates expectations. When substituting an active drug with a placebo, the context of treatment remains the same together with the expectations the patients have on the outcome of therapy. Therefore, the study of placebo is the study of the context in which a medical treatment takes place and of the effects that this context has on the patient’s brain (Carlino et al. 2014).

Several factors influence the expectations that patients develop, such as the verbal interactions with other patients or therapists, the emotions felt during treatment and the previous therapeutic experiences. For instance, the more “strong” the words used by the physician during the administration of a placebo lotion meant alleviate pain, the higher the expectations of pain reduction patients will have and, as a consequence, the stronger the analgesic effect they will feel after the application of the lotion. The reduction of anxiety that the patient feels when hearing the voice of the doctor, the activation of the reward system that corresponds to the anticipation of a clinical improvement, interact with expectations and contribute to the modification of the patient’s brain. Obviously, in each of these examples, we must always consider the role of the relationship between patient and doctor: the more trust and respect the patient feels toward his/her doctor, the more positive clinical changes will occur.

From a psychological standpoint, research showed that expectations are heavily influenced by past experiences. To explain this phenomenon we can refer to the classical example of Pavlovian conditioning. Such model states that after several exposures to a neutral stimulus (e.g. a sound) associated with an unconditioned stimulus (e.g. food), which by itself produces a response (salivation), presenting just the neutral stimulus will lead to the same response. It is possible to elicit placebo effect by using the same conditioning principles. For instance, it has been observed that certain specific aspects of a treatment, such as the shape of drugs, can induce conditioned placebo responses if that shape had been previously associated to effective active ingredients. That means that repeated administration of a treatment induces in patients specific expectations on the treatment itself: for example, the administration of morphine induces a reduction of pain and thus a future expectation of pain reduction for future administrations. Such expectations and predispositions make the treatment work even if it consists in a sugar pill. In a study that was conducted with functional magnetic resonance, it has been proved that the expectation of pain reduction is built with the passing of time: the more time passes, the less pain is felt, the more intense the activation of certain brain areas that seem to be implicated in processing expectations: more specifically the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the cingulate anterior cortex (Lui et al., 2010).

From the neurophysiological standpoint, the belief that what we receive is what we expect is increasingly supported by different researches. When a patient is expecting to receive an analgesic drug, he/she activates the brain pain modulatory system just as if he/she were receiving the drug. In many studies, researchers administered opioid painkillers, such as morphine or remifentanil. In such studies, after having purposely induced pain, the authors compared the brain activation caused by the administration of a painkiller (such as remifentanil) with that caused by the administration of a placebo that the patient considered a real analgesic. Results show that both groups (remifentanil group and placebo group) reported a reduction in pain levels. In the brain, the areas that were activated by the drug and by the placebo were very similar: in both cases a reduction in the activation of the brain areas involved in pain perception, that is a system called “pain matrix”, which includes the thalamus, the insula, the rostral part of the anterior cingulate cortex, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the primary somatosensory cortex, the supramarginal gyrus and the left parietal lobule. Furthermore, in the placebo group, a greater activation of frontal areas and of the above-mentioned prefrontal dorsolateral and anterior cingulate cortices has been observed (Petrovic et al., 2005, 2010). Such areas, in fact, are involved in the elaboration of superior brain functions, such as planning and abstract reasoning and have a crucial role in the processing of expectations.

Implications for clinical practice and hypnosis

Maybe, one of the most interesting demonstrations that expectation is a crucial factor in therapy comes from the researches using the so-called “open-hidden” protocol. Let’s picture a patient who is attached to an infusion pump that releases a specific anesthetic in certain moments of the day. The patient will know that the anesthetic will be released but he/she doesn’t know when (hidden). In this protocol, a therapy can be administered without providing any verbal information signaling the administration (open administration). Therefore the patient, doesn’t expect any kind of improvement and this absence of expectation leads to a true reduction of therapeutic effectiveness (Benedetti, Carlino & Pollo, 2011).

The open-hidden model suffers from the disadvantage of being very hard to apply from a methodological point of view but has the enormous advantage to lie on the border between experimental context and clinical practice. It has been demonstrated, for instance, that the effectiveness of diazepam, one of the most frequently used benzodiazepines in the treatment of anxious conditions, is greatly reduced or completely abolished when administered without the patient’s awareness, that is in a hidden modality (Benedetti, Carlino & Pollo, ibid.). Another “historical” example comes from dental practice: it has been observed that, after a third molar extraction, the anesthetic effects of an intravenous injection of 6-8 mg of morphine (hidden administration) corresponded to those generated by the injection of a saline solution (placebo) openly administered to the patient. In conclusion, when patients expected to receive an anesthetic, the effects were so strong that they felt the same effect of 6-8 mg of morphine.

From a clinical point of view, these studies lead to emphasize the idea that the knowledge the patient has about the treatment does influence the treatment itself. One could, for example, think to openly begin the administration of a drug, increasing its effectiveness, to then cease it according to a hidden protocol in order to reduce the negative expectations related to the end of the treatment. A recent survey on the Italian population showed that the most important preoccupation for patients in the sample is related to the doctor-patient relationship and, more specifically, it concerns the information about the effectiveness of the therapy that they are going to receive. In light of these studies, we should expect that all therapies that are not administered with adequate information and that do not create (ethical) positive expectations, will end up to be weakly effective for patients (Frisaldi & Piedimonte, 2014).

We must consider that the doctor-patient relationship is always influenced by words and attitudes that channel strong expectations toward the treatment program. Together with patients’ expectations, in fact, a better interaction with the doctor leads to better therapeutic adherence up to the point that the number of medical exams can be considered as an index to measure the improvement (for a review of the literature on the doctor-patient relationship: Benedetti, 2012). Therefore, the trust that patients feel toward their doctor, their opinion on his/her experience and also (maybe above all) the human relationship between them, are all factors that lead to more positive therapeutic outcomes.

About the connection between placebo and hypnosis, the latter may be used as a tool, explicitly used, to manage expectations in order to produce therapeutic effects. An interesting way to define hypnosis is that of a “non deceitful placebo” (Kirsh, 1994). Considering this definition and interpreting hypnosis in the frame of placebo effect, the crucial factor of therapeutic sessions may be constituted by the construction of a context that elicits placebo effects in patients without the use of “true” placebos and thus creating expectations towards change through verbal and contextual relationship.

Interestingly, several studies compared the effects of hypnosis with those caused by a placebo response in different clinical contexts. More specifically, it has been showed that both hypnosis and placebos produced comparable pain reductions in the treatment of headaches (Spanos et al, 1993). In studies targeting experimentally induced pain (where pain is “artificially” produced by means, for example, of a cuffthat tightens around the arm of participants), researchers showed that subjects who are less susceptible to hypnosis obtained similar pain reductions when receiving hypnosis or a placebo. On the contrary, patients who were highly susceptible to hypnosis showed a greater pain reduction after just one hypnosis session compared to that felt following the administration of a placebo (Frischholz, 2007).

Therefore, if on the one hand it seems that the effects generated by placebos and hypnosis are very similar, on the other, there surely are some substantial differences between the two mechanisms, unfortunately still poorly examined by scientific research.

From a neuroscientific point of view, neuro-imaging techniques (techniques that allow us to visualize the in-vivo activity of the brain) showed some interesting “cerebral parallels” between hypnosis and placebo effect. As highlighted in previous paragraphs, several studies have pointed to the relevant activation of the anterior cingulate cortex (area of emotion processing) and of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (which has a role in planning future complex behaviors) that occurrs during hypnosis sessions and these same areas appear to be active during placebo responses (Frisaldi & Piedimonte, ibid.).

Concerning the effects of hypnosis, it has been showed that these produce a brain pattern that consists primarily in the reduction of activity in a network called “default mode network” (McGeown et al. 2009). Such network, which includes frontal and subcortical structures, is constituted by a group of areas that are believed to be active when individuals are not involved in any specific cognitive task (problem solving, planning behavior, etc…) but, instead, they let their minds “wander” in a relaxed state. A reduction in the activity of these areas means an active shift of attention toward the suggestion the therapist is providing that, maybe, can reflect the construction of expectations on the session. This study in particular demonstrates that hypnosis is not a passive phenomenon in which there is a sender and a receiver, but, on the contrary, it is a constructive process where clients actively listen to the words of the therapist and build their hypotheses about the relationship.

The study of how mechanisms similar to the placebo response act and interact within the hypnotic phenomena, while being a big challenge, can lead us to understand which brain areas are involved in the generation of a positive expectation and, more generally, to develop approaches that can increasingly be tailored on patients to enhance the positive outcome of a (psycho)therapy.

References

Benedetti, Fabrizio, Elisa Carlino, and Antonella Pollo. “How Placebos Change the Patient’s Brain.” Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 36, no. 1 (January 2011): 339–54. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.81.

Carlino, Elisa, Elisa Frisaldi, and Fabrizio Benedetti. “Pain and the Context.” Nature Reviews Rheumatology 10, no. 6 (June 2014): 348–55. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2014.17.

Frisaldi, Elisa, Alessandro Piedimonte, and Fabrizio Benedetti. “Placebo and Nocebo Effects: A Complex Interplay Between Psychological Factors and Neurochemical Networks.” American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 57, no. 3 (July 3, 2015): 267–84. doi:10.1080/00029157.2014.976785.

Frischholz, Edward J. “Hypnosis, Hynotizability, and Placebo.” American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 50, no. 1 (July 1, 2007): 49–58. doi:10.1080/00029157.2007.10401597.

“Il Cervello Del Paziente - Benedetti Fabrizio - Libro - Giovanni Fioriti Editore - - IBS.” Accessed January 24, 2015. http://www.ibs.it/code/9788895930497/benedetti-fabrizio/cervello-del-paziente.html.

Levine, Jon D., Newton C. Gordon, Richard Smith, and Howard L. Fields. “Analgesic Responses to Morphine and Placebo in Individuals with Postoperative Pain.” PAIN 10, no. 3 (June 1981): 379–89. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(81)90099-3.

Lui, Fausta, Luana Colloca, Davide Duzzi, Davide Anchisi, Fabrizio Benedetti, and Carlo A. Porro. “Neural Bases of Conditioned Placebo Analgesia.” Pain 151, no. 3 (December 2010): 816–24. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.021.

McGeown, William J., Giuliana Mazzoni, Annalena Venneri, and Irving Kirsch. “Hypnotic Induction Decreases Anterior Default Mode Activity.” Consciousness and Cognition 18, no. 4 (December 2009): 848–55. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2009.09.001.

Spanos, Nicholas P., Sharon J. Liddy, Heather Scott, Catherine Garrard, Joy Sine, Angela Tirabasso, and Amber Hayward. “Hypnotic Suggestion and Placebo for the Treatment of Chronic Headache in a University Volunteer Sample.” Cognitive Therapy and Research 17, no. 2 (April 1, 1993): 191–205. doi:10.1007/BF01172965.